Empanada frita con vino tinto

Fabiola Burgos Labra

Risograph print with hand drawing interventions and digital color print

Printed at Frans Masareel Centrum, Kasterlee, and Color Impact, Brussels

Text by Carolina Arévalo

Translation by Shweta Venkat

Design by Felipe Mujica and Fabiola Burgos Labra

Printed on the occasion of Worldlines – Final Show 2023 HISK (Hoger Instituut Voor Schone Kunsten), curated by Sebastien Plout

Gosset, Rue Gabrielle Petit 4, 1080 Molenbeek -Saint-Jean, Brussels

November – December 2023

Fabiola Burgos Labra: The loss of the original

Carolina Arévalo

The art of collecting has been a human activity since time immemorial. It was the first revolution that enabled communities to take root in places. For example, the collection of seeds is an act of conservation and care of life itself, embracing within itself the potential to grow, flourish, and reproduce, with a recognition of human dependence on nature. This exhibition project by Fabiola Burgos Labra (born in Osorno, 1984) tackles the preservation, conservation, and loss of the original, while also stressing on the copy, seriality, quantity, and method of production.

The Ghent Branches series broaches places and acts as a medium of return to one’s own landscape. It starts with the reassembling of branches collected over the course of a day in different parts of the city of Ghent, where the artist lived and worked. Indeed, she feels that there are similarities between Ghent and her hometown of Osorno, in the south of Chile: ‘There is a much closer relationship with nature in my everyday life: walking to the workshop, passing through many parks, the constant rain, the smell of wet leaves; this job has more to do with the pleasure of collecting branches than anything else.’ The branches here represent the recognizable, a strategy of belonging. Burgos continues, “[the branches] are more or less the same size, I can carry them in my hand or in my suitcase: an approximate reference to how much they grow.’ These “branches” serve as units of measurement for things that cannot be measured – references to how things are spatially related. The five branches act as fingers extending to the earth. The segmentations in each are random but intuitive; there is no logic. They are connected to walking and are reminiscent of André Cadere’s Round Bar of Wood, a self-contained balance between repetition and anticipation. The differences in each branch are highlighted to create a feeling of alternation; there are different parts because it is a relationship with a system of things.

In Stilling Life, Burgos crochets clothes for pears before waiting for the fruit to rot from the inside. It is a sort of mummification of fruits. The fabric represents the living body – always unique – at the top of the pear, which then remains empty and is modified by the integration of the decaying organic material within. This organic unexpectedness of life continues in the piece Hongos, a series of exercises where the artist grows fungus in coffee inside plastic bags and random objects that were previously cut in an attempt to steer their growth. Nature resists and grows spontaneously following its own logic. The relationship of the material encounter between the inert plastic container and the fibrous and lush fungus is contradictory but mutual.

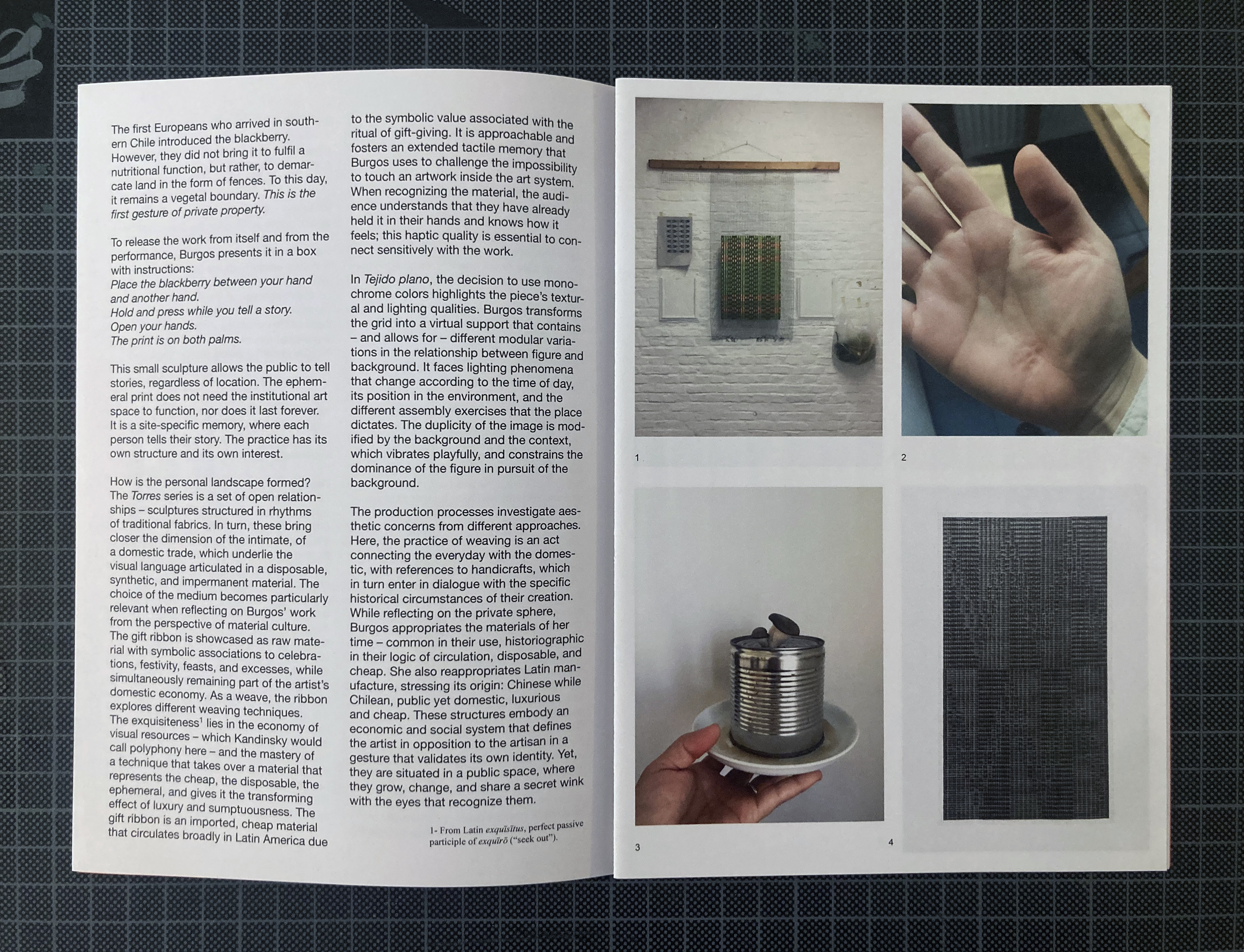

Ways to Return Home begins with the collection of blackberries for the subsequent creation of a mould and its casting in bronze. The act of picking fruit is something common to everyone, that unites us. During the moulding process, the blackberry is lost, thereby questioning the so-called original. Only one cast is made for each sample. The bronze piece remains raw and unfinished; it is not a piece of jewellery. Burgos then applies black shoe polish to the final piece. This technique is used to increase the bronze shine when it will later be polished by the constant friction of fingers. In this way, the more people tell stories with their blackberries, the brighter the objects become – ‘but they have to realize that’ says the artist. This artwork started as an exercise on series, but, due to its volumetric and textural qualities, it becomes imprinted ephemerally on the user’s hand. It resists the relationship of time and production; it states the natural cycles of things.

The first Europeans who arrived in southern Chile introduced the blackberry. However, they did not bring it to fulfil a nutritional function, but rather, to demarcate land in the form of fences. To this day, it remains a vegetal boundary. This is the first gesture of private property. To release the work from itself and from the performance, Burgos presents it in a box with instructions:

Place the blackberry between your hand and another hand.

Hold and press while you tell a story.

Open your hands.

The print is on both palms.

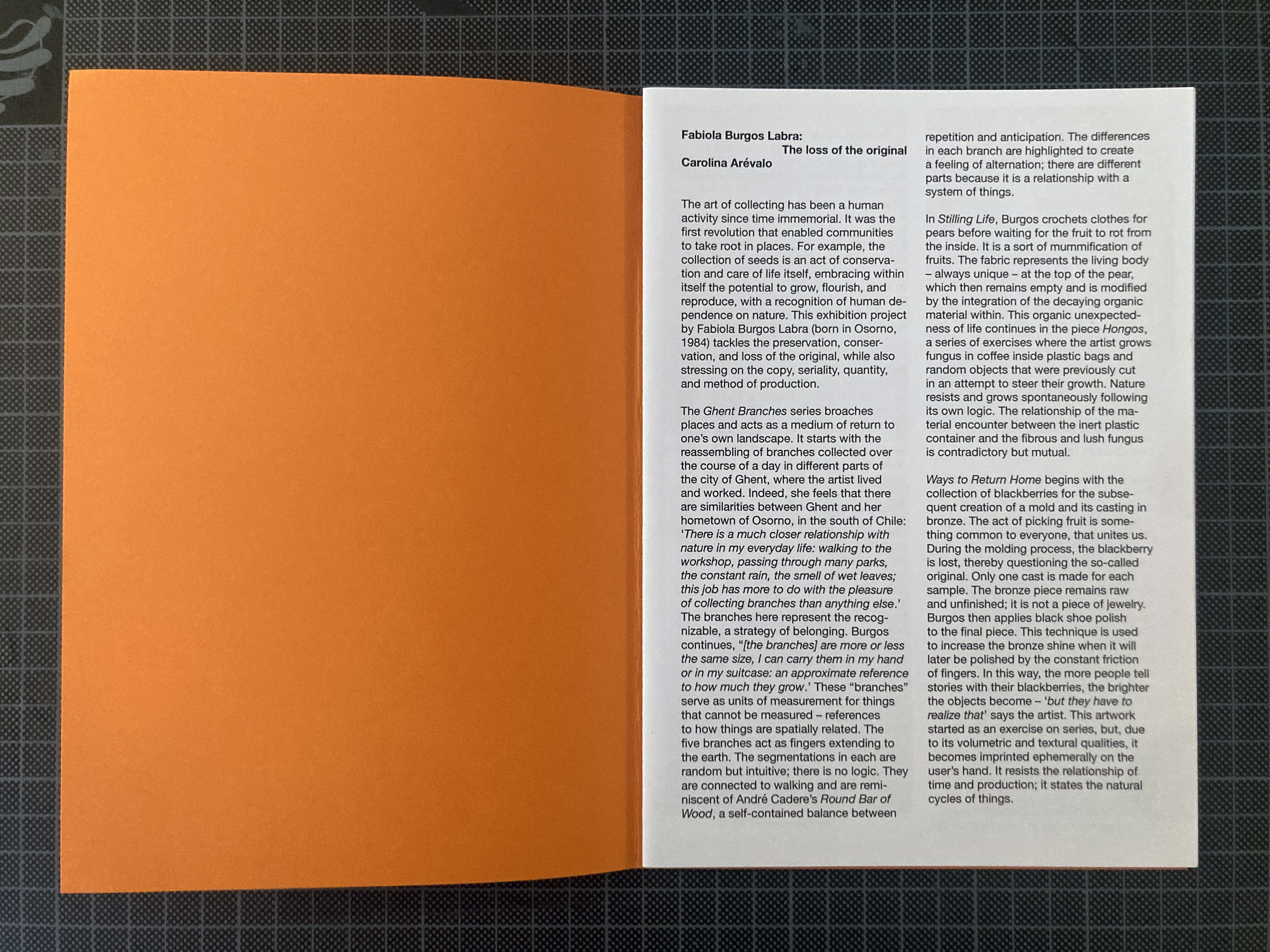

This small sculpture allows the public to tell stories, regardless of location. The ephemeral print does not need the institutional art space to function, nor does it last forever. It is a site-specific memory, where each person tells their story. The practice has its own structure and its own interest. How is the personal landscape formed? The Torres series is a set of open relationships – sculptures structured in rhythms of traditional fabrics. In turn, these bring closer the dimension of the intimate, of a domestic trade, which underlie the visual language articulated in a disposable, synthetic, and impermanent material. The choice of the medium becomes particularly relevant when reflecting on Burgos’ work from the perspective of material culture.

The gift ribbon is showcased as raw material with symbolic associations to celebrations, festivity, feasts, and excesses, while simultaneously remaining part of the artist’s domestic economy. As a weave, the ribbon explores different weaving techniques. The exquisiteness1 lies in the economy of visual resources – which Kandinsky would call polyphony here – and the mastery of a technique that takes over a material that represents the cheap, the disposable, the ephemeral, and gives it the transforming effect of luxury and sumptuousness. The gift ribbon is an imported, cheap material that circulates broadly in Latin America due to the symbolic value associated with the ritual of gift-giving. It is approachable and fosters an extended tactile memory that Burgos uses to challenge the impossibility to touch an artwork inside the art system.

When recognizing the material, the audience understands that they have already held it in their hands and knows how it feels; this haptic quality is essential to connect sensitively with the work. In Tejido plano, the decision to use monochrome colors highlights the piece’s textural and lighting qualities. Burgos transforms the grid into a virtual support that contains – and allows for – different modular variations in the relationship between figure and background. It faces lighting phenomena that change according to the time of day, its position in the environment, and the different assembly exercises that the place dictates. The duplicity of the image is modified by the background and the context, which vibrates playfully, and constrains the dominance of the figure in pursuit of the background.

The production processes investigate aesthetic concerns from different approaches. Here, the practice of weaving is an act connecting the everyday with the domestic, with references to handicrafts, which in turn enter in dialogue with the specific historical circumstances of their creation. While reflecting on the private sphere, Burgos appropriates the materials of her time – common in their use, historiographic in their logic of circulation, disposable, and cheap. She also reappropriates Latin manufacture, stressing its origin: Chinese while Chilean, public yet domestic, luxurious, and cheap. These structures embody an economic and social system that defines the artist in opposition to the artisan in a gesture that validates its own identity. Yet, they are situated in a public space, where they grow, change, and share a secret wink with the eyes that recognize them.

Fabiola Burgos Labra

Risograph print with hand drawing interventions and digital color print

Printed at Frans Masareel Centrum, Kasterlee, and Color Impact, Brussels

Text by Carolina Arévalo

Translation by Shweta Venkat

Design by Felipe Mujica and Fabiola Burgos Labra

Printed on the occasion of Worldlines – Final Show 2023 HISK (Hoger Instituut Voor Schone Kunsten), curated by Sebastien Plout

Gosset, Rue Gabrielle Petit 4, 1080 Molenbeek -Saint-Jean, Brussels

November – December 2023

Fabiola Burgos Labra: The loss of the original

Carolina Arévalo

The art of collecting has been a human activity since time immemorial. It was the first revolution that enabled communities to take root in places. For example, the collection of seeds is an act of conservation and care of life itself, embracing within itself the potential to grow, flourish, and reproduce, with a recognition of human dependence on nature. This exhibition project by Fabiola Burgos Labra (born in Osorno, 1984) tackles the preservation, conservation, and loss of the original, while also stressing on the copy, seriality, quantity, and method of production.

The Ghent Branches series broaches places and acts as a medium of return to one’s own landscape. It starts with the reassembling of branches collected over the course of a day in different parts of the city of Ghent, where the artist lived and worked. Indeed, she feels that there are similarities between Ghent and her hometown of Osorno, in the south of Chile: ‘There is a much closer relationship with nature in my everyday life: walking to the workshop, passing through many parks, the constant rain, the smell of wet leaves; this job has more to do with the pleasure of collecting branches than anything else.’ The branches here represent the recognizable, a strategy of belonging. Burgos continues, “[the branches] are more or less the same size, I can carry them in my hand or in my suitcase: an approximate reference to how much they grow.’ These “branches” serve as units of measurement for things that cannot be measured – references to how things are spatially related. The five branches act as fingers extending to the earth. The segmentations in each are random but intuitive; there is no logic. They are connected to walking and are reminiscent of André Cadere’s Round Bar of Wood, a self-contained balance between repetition and anticipation. The differences in each branch are highlighted to create a feeling of alternation; there are different parts because it is a relationship with a system of things.

In Stilling Life, Burgos crochets clothes for pears before waiting for the fruit to rot from the inside. It is a sort of mummification of fruits. The fabric represents the living body – always unique – at the top of the pear, which then remains empty and is modified by the integration of the decaying organic material within. This organic unexpectedness of life continues in the piece Hongos, a series of exercises where the artist grows fungus in coffee inside plastic bags and random objects that were previously cut in an attempt to steer their growth. Nature resists and grows spontaneously following its own logic. The relationship of the material encounter between the inert plastic container and the fibrous and lush fungus is contradictory but mutual.

Ways to Return Home begins with the collection of blackberries for the subsequent creation of a mould and its casting in bronze. The act of picking fruit is something common to everyone, that unites us. During the moulding process, the blackberry is lost, thereby questioning the so-called original. Only one cast is made for each sample. The bronze piece remains raw and unfinished; it is not a piece of jewellery. Burgos then applies black shoe polish to the final piece. This technique is used to increase the bronze shine when it will later be polished by the constant friction of fingers. In this way, the more people tell stories with their blackberries, the brighter the objects become – ‘but they have to realize that’ says the artist. This artwork started as an exercise on series, but, due to its volumetric and textural qualities, it becomes imprinted ephemerally on the user’s hand. It resists the relationship of time and production; it states the natural cycles of things.

The first Europeans who arrived in southern Chile introduced the blackberry. However, they did not bring it to fulfil a nutritional function, but rather, to demarcate land in the form of fences. To this day, it remains a vegetal boundary. This is the first gesture of private property. To release the work from itself and from the performance, Burgos presents it in a box with instructions:

Place the blackberry between your hand and another hand.

Hold and press while you tell a story.

Open your hands.

The print is on both palms.

This small sculpture allows the public to tell stories, regardless of location. The ephemeral print does not need the institutional art space to function, nor does it last forever. It is a site-specific memory, where each person tells their story. The practice has its own structure and its own interest. How is the personal landscape formed? The Torres series is a set of open relationships – sculptures structured in rhythms of traditional fabrics. In turn, these bring closer the dimension of the intimate, of a domestic trade, which underlie the visual language articulated in a disposable, synthetic, and impermanent material. The choice of the medium becomes particularly relevant when reflecting on Burgos’ work from the perspective of material culture.

The gift ribbon is showcased as raw material with symbolic associations to celebrations, festivity, feasts, and excesses, while simultaneously remaining part of the artist’s domestic economy. As a weave, the ribbon explores different weaving techniques. The exquisiteness1 lies in the economy of visual resources – which Kandinsky would call polyphony here – and the mastery of a technique that takes over a material that represents the cheap, the disposable, the ephemeral, and gives it the transforming effect of luxury and sumptuousness. The gift ribbon is an imported, cheap material that circulates broadly in Latin America due to the symbolic value associated with the ritual of gift-giving. It is approachable and fosters an extended tactile memory that Burgos uses to challenge the impossibility to touch an artwork inside the art system.

When recognizing the material, the audience understands that they have already held it in their hands and knows how it feels; this haptic quality is essential to connect sensitively with the work. In Tejido plano, the decision to use monochrome colors highlights the piece’s textural and lighting qualities. Burgos transforms the grid into a virtual support that contains – and allows for – different modular variations in the relationship between figure and background. It faces lighting phenomena that change according to the time of day, its position in the environment, and the different assembly exercises that the place dictates. The duplicity of the image is modified by the background and the context, which vibrates playfully, and constrains the dominance of the figure in pursuit of the background.

The production processes investigate aesthetic concerns from different approaches. Here, the practice of weaving is an act connecting the everyday with the domestic, with references to handicrafts, which in turn enter in dialogue with the specific historical circumstances of their creation. While reflecting on the private sphere, Burgos appropriates the materials of her time – common in their use, historiographic in their logic of circulation, disposable, and cheap. She also reappropriates Latin manufacture, stressing its origin: Chinese while Chilean, public yet domestic, luxurious, and cheap. These structures embody an economic and social system that defines the artist in opposition to the artisan in a gesture that validates its own identity. Yet, they are situated in a public space, where they grow, change, and share a secret wink with the eyes that recognize them.